Woodrow Wilson’s second term revolved around America’s entry into the Great War. Would his leadership earn the Democrats another four years in the presidency? Or would the isolationist backlash revive the Republicans?

The Last Four Years

A lot changed between the Election Day 1916 and Wilson’s second inauguration in March. The campaign slogan, “He kept us out of war,” was quickly forgotten. Germany resumed its unrestricted submarine warfare, threatening American trade. With the release of the Zimmerman Telegram, they were caught red-handed inviting Mexico to an alliance against the US. On April 2, 1917, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war. It passed overwhelmingly.

Wilson appointed General John Pershing, who had recently chased Pancho Villa back into Mexico, as head of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Although it took a year of organizing before the US could send a significant number of troops to Europe, Wilson’s wartime legislation was swift and thorough. The Selective Service Act made the draft official on May 18th. The War Industries Board was created to control manufacturing and railroads were placed under the authority of the Secretary of Treasury. The National War Labor Board, which included former President William H. Taft, mediated labor disputes to avoid disruptions in productivity. Other new organizations included the Fuel Administration, led by President James Garfield’s son, Harry, and the Food Administration, led by businessman Herbert Hoover, who was already known for leading food relief efforts to Europe. Controversially, Wilson also cracked down on anti-war sentiment. The Committee on Public Information used all forms of media to promote the war effort. The Espionage Act, Trading with the Enemy Act, and Sedition Act made public opposition to the war illegal. Lastly, to pay for the war, Wilson raised taxes.

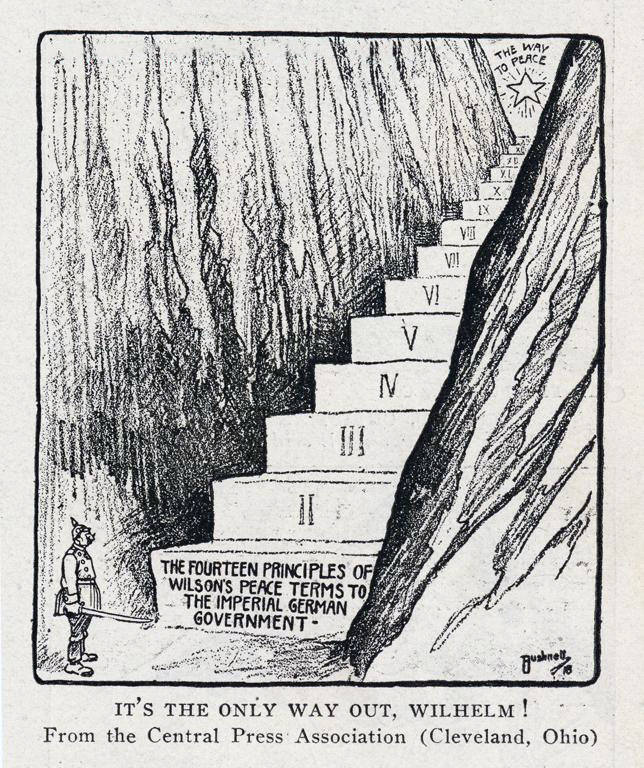

By the summer of 1918, 10,000 American troops were arriving in Europe every day. This boost to the Allied effort finally compelled Germany to surrender. The war came to an end on November 11, 1918. The terms of surrender were based on Wilson’s outline for peace, known as the Fourteen Points. The world’s leading nations met in January 1919 to begin work on the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson, having earned a seat at the negotiating table, was eager to push for his grand vision of a worldwide peacekeeping coalition, the League of Nations. He believed the League would resolve any faults with the Fourteen Points and prevent future wars. Unfortunately, while Wilson was focused on winning over European leaders, he was losing support in the US. Democrats did poorly in the 1918 midterms and Republicans took back control of Congress. They were offended when Wilson failed to select any Republicans for his peace conference commission. Consequently, Republicans were ready to strike down any treaty that Wilson brought back. They argued that the League of Nations would infringe on US sovereignty and commit the country to fight in future European wars.

To increase support for the League, Wilson went on a nation-wide tour. The trip was cut short, however, when he collapsed in Pueblo, Colorado, in September 1919. He quickly returned to the White House, and had a paralytic stroke on October 2nd. His wife of four years, Edith, hid his condition from the public and from government officials. Along with Wilson’s personal secretary, Joseph Tumulty, she helped carry out the president’s duties. Vice President Thomas Marshall was pressured to take over as president, but since the rules of succession were still not clear, he did not act on the impulse. Despite his ill state, Wilson continued to be uncompromising on the League of Nations. The Treaty of Versailles, and the League, failed to pass Congress in November. Wilson still received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1920 for his efforts.

Wilson also faced several domestic challenges. After the war, soldiers returned to the job market and manufacturing slowed, dragging the US into an economic recession. There were major labor strikes in the steel, coal, and meat-packing industries. There was an increase in race riots and lynching. A series of anarchist bombings and the October Revolution in Russia led to a fear of Communism and the first “Red Scare.” To make matters worse, the world was hit with the 1918 Flu Pandemic, which killed over 600,000 Americans. While there are several theories as to the flu’s source, it was colloquially known as the “Spanish Flu” because Spain, having remained neutral in the war, did not have a propaganda division to deflect blame. There were two additional major pieces of legislation in Wilson’s second term. Prohibition, the 18th Amendment, gained popularity as temperance groups had increasing influence on members of Congress. Wilson actually vetoed the Volstead Act, which provided prohibition’s means of enforcement, but it was over-turned by Congress. Lastly, women’s suffrage, the 19th Amendment, was ratified in 1920! Wilson had privately supported women’s voting rights for years, but believed it to be a states’ rights issue. Changing roles for women during the war led to increased support for the long-overdue change.

Major Issues

The 1920 election was clearly understood to be a referendum of the League of Nations, and of Wilson’s legacy. Few people shared his idealism for American-led peace and many resented his wartime controls. By the end of his term, the average voter’s daily reality was high cost of living and high unemployment.

Party Watch & The Candidates

Democrats remained loyal to Wilson. They endorsed the League of Nations in their platform. Many politicians hoped to be his successor. An early favorite was former Secretary of Treasury William McAdoo, coincidentally Wilson’s son-in-law. Wilson blocked his nomination, hoping that a contested convention might lead to a third term. But the party knew Wilson was unpopular and ill. Vice President Thomas Marshall hoped to run, too, but he faced criticism for his inability to succeed Wilson after his stroke. On the 44th ballot, the convention eventually settled on dark-horse candidate James M. Cox, the moderately progressive governor of ohio. Cox also owned the Dayton Daily News (and eventually, a media conglomerate that became Cox Enterprises, one of the largest cable TV providers in the US). His running mate was the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, best known as Teddy Roosevelt’s fifth cousin. Franklin admired his cousin’s political style in his youth and, similarly, served as a boss-fighting progressive in the New York state government. Keeping with tradition for his side of the Roosevelt family, Franklin remained a Democrat.

The Republicans were confident of victory in November, but in the meantime, there were few outstanding choices for the nomination. Sadly, Teddy Roosevelt died in 1919. He left no heir-apparent for the progressive wing of the party. The convention was in a deadlock between Major General Leonard Wood, the true commander of the Rough Riders that was passed up by Wilson as commander of the AEF; and Illinois Governor Frank Lowden, best known for his handling of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. Delegates were tired and hot and wanted to wrap things up, so they settled on another dark-horse, newspaper-owning ohioan, Senator Warren G. Harding. Harding was popular and had no political enemies. He was seen as a small-town, self-made businessman who could appeal to voters’ nostalgia. As Senator Frank Brandegee put it, “There ain’t any first-raters this year… We got a lot of second-raters and Warren Harding is the best of the second-raters.” Rumors of crooked deals spread after a reporter caught Harding’s campaign manager, Harry Daugherty, checking out of his hotel. The reporter ran the (likely embellished) quote from Daugherty, “I don’t expect Senator Harding to be nominated on the first, second, or third ballots, but I think we can afford to take chances that about eleven minutes after two, Friday morning of the convention, when fifteen or twelve weary men are sitting around a table, someone will say, ‘Who will we nominate?’ At that decisive time, the friends of Harding will suggest him and we can well afford to abide by the result.” The myth of fifteen men selecting a candidate in a smoke-filed room stuck. Harding’s running mate was Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge, most famous for breaking a police strike in Boston in 1919. The Republican platform was anti-Wilson and Anti-League of Nations, though it still called for an “agreement among nations to preserve peace.”

After taking one presidential election off, Eugene Debs was back to run as the Socialist Party candidate. This time, he was running from prison! Thanks to Wilson’s harsh restrictions on speech, Debs was convicted for sedition due to his anti-war rhetoric.

The Campaign

Cox chose the increasingly popular national-tour style of campaigning. Harding mostly stuck with the old-style front porch campaign from Marion, ohio. When he did take the stump, he struggled. During one pre-written speech, he stumbled over a passage, paused, and told the audience, “Well, I never saw this before. I didn’t write this speech and don’t believe was I just read.” Harding’s attacks were primarily directed at Wilson, not Cox. He appealed to voters’ desire to return to the good ol’ days of the late Nineteenth Century, when Republicans ran the federal government. At a speech in Boston, Harding said, “America’s present need is not heroics but healing; not nostrums but normalty; not revolutions but restoration; not surgery but serenity.” Per his manuscript, he was supposed to use the word normality, but misspoke. Reporters translated the made-up word to the better-sounding “normalcy.” Thus, the campaign had a new slogan, “Return to normalcy.” What voters didn’t know was that, behind Harding’s call for small-town values, he personally had many vices. He chewed tobacco, gambled, drank alcohol (despite prohibition), and had extra-marital affairs. In fact, the party paid for his mistress and her husband to travel to Asia during the campaign. Some of Harding’s nastiest opponents spread the rumor that he was secretly a descendent of African Americans. Wilson and Cox opposed using the accusation for the campaign. Harding was convinced by Republican Party officials, and his wife, to not comment.

One major milestone of this election was the first ever presidential poll! The Literary Digest mailed out millions of postcards asking for voters’ preferences. Their results predicted a Harding victory by a wide margin.

Election Day

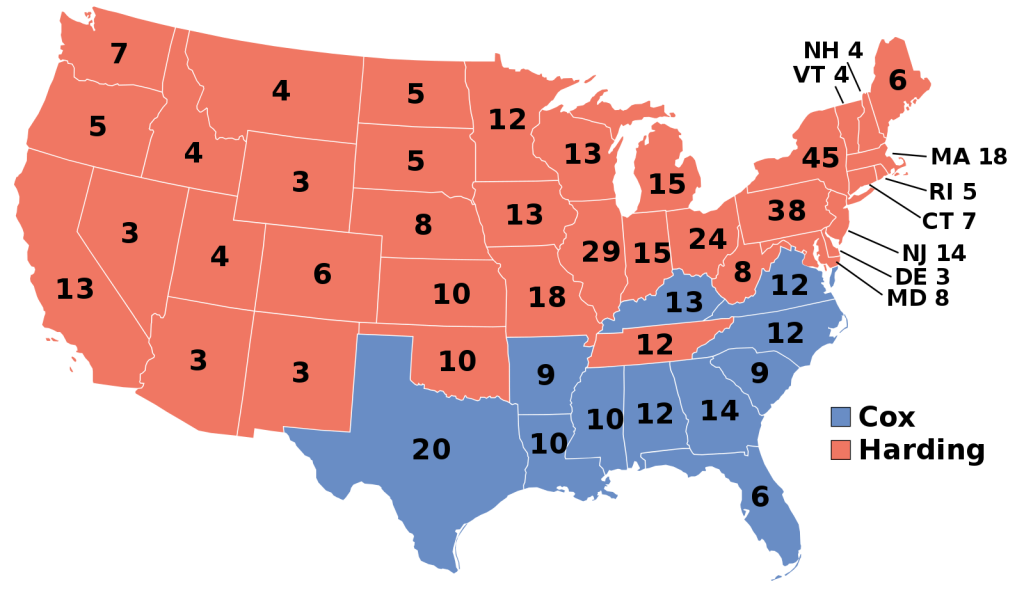

Wilson’s secretary, Joseph Tumulty, said of the election, “It wasn’t a landslide, it was an earthquake.” Harding won every state outside of the Solid South, plus Tennessee. It was the first time a Republican won a former Confederate State since Reconstruction. Turnout was low, as most voters predicted this outcome. Turnout was also low for women voters, who were not yet used to voting, outside of the West. Cox didn’t get any help from immigrant groups that normally voted Democratic. Irish and German Americans in Northern urban centers resented Wilson for siding with the British and believed their home countries had been taken advantage of in postwar treaties.

Despite running from prison, Eugene Debs received over 900,000 votes!

The Winner

Warren G. Harding won! He was America’s 29th president. The electoral score was 404-127. With over 16 million votes (60%), Harding obliterated Cox’s 9 million. Harding surpassed Teddy Roosevelt for the largest victory since James Monroe’s uncontested run one hundred years earlier.

What Did It Say About America?

Wilson wanted the election to be a referendum on the League of Nations, but it was mostly a rejection of a failing president. The Democratic-leaning New York World said the result was due to voters’ “resentment… for anything and everything they had found to complain of in the last eight years.” Harding’s “return to normalcy” attracted people who were struggling with the complex, postwar culture. Ironically, it was traditionally Republicans who wanted the US to have a greater presence on the world stage, but they would rather promote isolationism than agree with Wilson.

Was It The Right Decision?

Nope! Democrats of this era don’t get a lot of love from me, but the Republicans wasted an easy win on a terrible president. Harding was boring, promoted a false sense of nostalgia, and would go on to lead one of the most corrupt administrations in American history. But between you and me, I don’t think we’ve seen the last of these running mates.